I just returned from being away on vacation with a friend in New Zealand and Australia for the last 3.5 weeks. In case you also want to follow that trip, here's a link to the newest blog: www.bergersadventures7.blogspot.com

A view of the atrium in our wonderful Sevilla hotel:

On arrival at the mill, the earth was crushed, placed in ponds, then mixed with water, beaten, sifted and left to rest until a large part of its moisture evaporated. To achieve consistency, the clay was extracted from these deposits and kneaded with the feet to form blocks that were then stored in a damp place so that organic residues were slowly destroyed. Before using the clay, it was kneaded again but with the heels of hands to create the pieces.

The pottery was turned on the pottery wheel and also formed with a clay laminate pressed into a plaster mold. The flat tiles and the reliefs were manufactured in a special press that was able to transfer the relief to the tile.

The vases, once released from the molds, were placed on long benches on which they were left to 'air' for a certain period of time so that the most intense moisture could slowly evaporate before the pieces were placed into the kiln. Once aired they were carefully placed in the firing chamber. Careful placement avoided accidental falls during the process and, leaving the air and fire to flow, made maximum use of the kiln space.

Once loaded, the oven was closed with brick and adobe and the fire action started, gentle and slow with just smoke at first, and then more intense and lean at the end. This process took between 12 and 15 hours and had to be controlled so that the ceramics were fired correctly. The final cooling had to be slow in order to avoid sharp changes in temperatures that could damage the pieces due to sudden contraction.

The colors of the flames coming out of the flame vents revealed when the items would be finished. The yellower and whiter the flames (which could be up to three feet high!) indicated the more advanced the process was.

The fuel used in the kilns in Triana has changed over the centuries. In the past it was olive branches used for golden pottery. Nowadays, pine and eucalyptus firewood has most often been used.

This and other murals were made by reusing baked pieces from an old ceramics factory in Triana.

This firm was created in 1939 and was built over a pottery workshop that had been active since the Middle Ages and had since became the Triana Ceramics Center. Painted pottery and the design for altarpieces were this company's specialty although they also decorated several types of tiles crafted using the old dry-string and edge techniques.

In comparison to the wood and metal that are most popular in the Nordic-European world, clay was the material used in the Mediterranean world to make household implements and pottery as well as many decorative architectural elements. Although glazed pottery originated in the Roman Empire, its production increased dramatically in Triana during the period of Islamic rule, particularly when Sevilla became of the capitals in the Almohad Empire in the 12th century. During the subsequent Christian era which began in Sevilla in 1248 and good relations with the Kingdom of Granada that remained under Muslim rule for another 250 years, this tradition was revived and strengthened in Sevilla, especially with regard to architectural uses.

The huge strides forward achieved by Mudejar ceramics reached new heights in Sevilla with the arrival of Niculoso Francisco Pisano in 1529. He was a potter trained in Italy who then lived, worked and died in Triana. Niculoso imbued Triana ceramics with the demanding thoroughness of his academic training, his knowledge of Renaissance decoration and his acute commercial acumen. He painted tiles in the Italian style for powerful customers, but also manufactured a semi-industrial product called arista tiles. They were press-mounted relief tiles which were mass produced and traded.

This spectacular printed and illuminated tile panel was created in 1880.

After learning almost more than we ever wanted to know about ceramics, I needed a tile shopping fix and there were plenty of ceramics shops nearby to satisfy that! Steven and I both had fun popping in and out of several shops that had just gorgeous selections of products made of tiles. After much deliberation, we ended up buying our house numbers with blank tiles on either end and all set in a plaque. Luckily they arrived home safe and sound but they have yet to see the light of day since then - hopefully they'll get put up soon on the front of the house, right Steven?!

This was one of the many traditional neighborhood grocers we passed that also functioned as neighborhood bars.

The Chapel of St. Francis had a sublime platersque or richly ornate altarpiece in the silversmith's style from the last third of the 16th century. It incorporated anonymous panels showing the stigmatization of St. Francis of Assisi, of St. Peter, the decapitation of St. John the Baptist and St. Jerome.

We'd just attended a three-person flamenco ensemble the night before in an intimate venue but I enjoyed this impromptu performance almost as much.

The Lord's Resurrection, circa 1650-1660, was taken to the Alcazar in 1810 and then onto Paris before being returned to Sevilla where it was kept for teaching purposes.

The Penitent Magdalene, painted around 1650, was the first picture to be confiscated by customs officials in compliance with regulations forbidding the export of works of art. Just two years after his arrival in Spain, King Charles III had signed a royal decree banning the export of paintings and sculptures by famous artists who were already deceased.

I think we were both pretty happy to see the 1863 map of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Brazil as we knew even last December that we'd be visiting Paraguay for ten days this coming December after taking a cruise in both Antarctica and Patagonia.

A view of the atrium in our wonderful Sevilla hotel:

The very attractive square outside of our hotel:

We headed to the Hospital de la Caridad, thankfully not because we required medical care but to see the charity hospital which functioned as a final place of refuge for Sevilla's poor and homeless. It was founded in the 17th century by the nobleman Don Miguel Manara, a major playboy and, according to Rick Steves, "an enthusiastic sinner who, late in life, had a major change of heart. He spent the last years of his life dedicating his life to strict worship and taking care of the poor."

Manara may well have been the inspiration for Don Juan, the character from a play set in 17th century Sevilla that was later made popular in Lord Byron's poetry and Mozart's opera Don Giovanni - "Don Juan" in Spanish. The working charity was unfortunately closed when we stopped by so we couldn't see Manara's office and a church filled with powerful art. I would have liked to see the church as the duty of the order of monks was to give a Christian burial to the executed and drowned.

It also would have been interesting to see Manara's tombstone outside the church's first entrance that has served as a welcome mat since 1679. He requested to be buried there where everyone would step o him as they entered. I read that it was marked "the worst man in the world."

Sevilla's historic riverside Torre del Oro was the starting and ending point for all shipping to the New World. It was named for the golden tiles that once covered it and not for the New World booty that arrived here! It has been a part of the city's fortifications ever since it was built by the Moors in the 13th century. Read more below about the controversy concerning the very tall tower in the background.

Across from the Gold Tower was Sevilla's Bullring and Bullfight Museum. We only admired it from the outside as we'd just recently spent quite a bit of time touring the bullring and museum in Ronda. There was likewise a chapel in the Sevilla bullring where matadors pray before their fights. I read that there have been no deaths in three decades in Sevilla's bullring thanks to the ready availability of blood transfusions. You might be interested to know the city was so appalled when the famous matador Manolette was killed in 1947 that even the mother of the bull that gored him was destroyed!

Many Spanish girls find matadors are such heartthrobs in their 'suits of light' that they have their bedrooms wallpapered with posters of cute bullfighters!

Across from the bullring was the Puente de Isabel II whose distinctive design with the circles under each span was inspired by an 1834 crossing over the Seine River in Paris. In Sevilla, as in many other European cities that grew up in the age of river traffic, what was long considered the 'wrong side of the river' had become the most colorful part of town.

We had a pretty view as we walked across the Guadalquivir River to explore Triana, described as a proud neighborhood that identifies with its working class origins and is known for its flamenco soul.

The city's only skyscraper, the Sevilla Tower, was designed by Argentine architect Cesar Pelli who also created Malaysia's humongous Twin Towers. According to city law, no structure could be taller than the Giralda Bell Tower on the Sevilla Cathedral. But because the building was not in the city center, the developers found a way to skirt the regulation. UNESCO considered putting the Seville's monuments that have been classified as World Heritage Sites (the Cathedral, Alcazar and Archivo de Indias) into the "Threatened List," because of the tower's “negative visual impact” on the old town skyline of Seville. UNESCO even asked the city to reduce the tower's height, but city officials ignored the requests.

At the end of the bridge was the beautiful Capilla del Carmen which was designed by the 1929 Expo architect to add glamour to Triana's entrance.

Just off the bridge and down the staircase was the Castillo de San Jorge, a 12th century castle that was the headquarters of Sevilla's Inquisition in the 15th century. In the castle's ruins was the neighborhood's covered market that was built in 2005 in the Moorish Revival style. Steven and I are always huge fans of markets so we made a beeline for it.

The market bustled with traditional fruit and vegetable stalls as well as a few meat shops.

This was the first time I remembered spotting signs made out of tiles in a market. That soon made sense, though, as Triana is famous for its ceramics.

These had to be about the largest tomatoes I've ever seen and they were organic!

This Christmas 'tree' was made of from cases of Cruzcampo, a major beer brand in Andalucia.

Loved these cute signs advertising tapas bars.

A major reason we'd come to Triana was to visit its ceramics shops and learn about the area's history as the center for ceramics.

To learn more about the history of ceramics, we toured the Museo de la Ceramica de Triana which focused on tile and pottery production.

The Spanish word of Islamic origin almagenas was given to the large jars that stored the liquid pigments ready for the painters to use in their work. Each one contained a different color.

The Muffle Furnace was a small kiln used to fire delicate and artistic pieces that required special conditions and temperatures.

The wheel and molds were the main methods used to form large pieces. When placed on drying shelves, the pieces lost part of their humidity before being put in the kiln.

The clay used in Triana was made up of two types of earth that were transported to the pottery mule by mule. The first was called antilla or blue clay - it was very organic, malleable and was extracted from the banks of the Guadalquivir River we'd just walked across.

The other one was called lizard clay as it was the same color as lizard skin. It was often extracted on the slopes of nearby villages where deep veins were exposed by the cut of the land. When this light clay with a refractory nature was mixed with the blue clay, it could be easily worked and fired without cracking problems.

On arrival at the mill, the earth was crushed, placed in ponds, then mixed with water, beaten, sifted and left to rest until a large part of its moisture evaporated. To achieve consistency, the clay was extracted from these deposits and kneaded with the feet to form blocks that were then stored in a damp place so that organic residues were slowly destroyed. Before using the clay, it was kneaded again but with the heels of hands to create the pieces.

The pottery was turned on the pottery wheel and also formed with a clay laminate pressed into a plaster mold. The flat tiles and the reliefs were manufactured in a special press that was able to transfer the relief to the tile.

The colors of the flames coming out of the flame vents revealed when the items would be finished. The yellower and whiter the flames (which could be up to three feet high!) indicated the more advanced the process was.

The fuel used in the kilns in Triana has changed over the centuries. In the past it was olive branches used for golden pottery. Nowadays, pine and eucalyptus firewood has most often been used.

Before the ceramics can be painted, they must be covered with a slightly thickish liquid called a yeast. It is made up of several mineral elements that are first ground, charred in the fire, crushed again and then mixed and dissolved in water. The colors are mineral oxides that produce a certain color in each case when they are melted in the firing. These oxides must be mixed with bindings and solvents, charred, ground and dissolved in liquid and applied by brushing on the enamel.

Other techniques, lost since the Middle Ages, were recovered and adapted to new requirements and improved thanks to chemical and industrial engineering advances. Once the pieces were decorated with a selected procedure, they were fired for a second and sometimes a third time to achieve the final product.

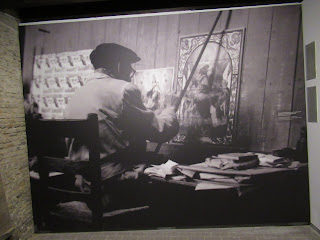

Many different painting ceramic procedures are practiced in Triana which, thanks, to continuous personnel changes, were known in all factories, although each factory specialized in certain products. Italian style brush painting was perfected at the beginning of the 20th century which was executed over raw enamel, added to the painting over fired enamel and executed with colors dissolved in essence of turpentine.

The remains of an old kiln, together with other buried kilns, were discovered during excavation on the site prior to the construction of the museum. According to archaeological studies, the kiln dated back to the 16th century although its structure was based on the shape of a Roman type of kiln.

Since the production of ceramics involve high emissions of noxious fumes, factories were generally established outside of cities. During the 12th century, Sevilla's ceramics factories were usually constructed on the far banks of the Guadalquivir River. From then until the 20th century, Triana was the most important hub of pottery production in Andalucia and one of the most active in all of Spain. In the 1920s, more than 20 ceramics factories were operating in Sevilla with the zenith being the years before the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition. Though none of them are still operating today, they all contributed to make the Triana name known in the world of ceramics.

Arista tiles from the first half of the 16th century:

During the 16th century, there was a large community of Italians and Flemish in Sevilla who were tied to activities at the city's port. It was the potters from these two areas that carried on and made the Italian painted ceramic technique endure. Pottery painters from that period left an era of magnificent tiled pieces.

The painted tile panel of Jesus Carrying the Cross was made in 1903.

After learning almost more than we ever wanted to know about ceramics, I needed a tile shopping fix and there were plenty of ceramics shops nearby to satisfy that! Steven and I both had fun popping in and out of several shops that had just gorgeous selections of products made of tiles. After much deliberation, we ended up buying our house numbers with blank tiles on either end and all set in a plaque. Luckily they arrived home safe and sound but they have yet to see the light of day since then - hopefully they'll get put up soon on the front of the house, right Steven?!

It was fun wandering down Calle San Jacinto as it had recently become a pedestrian street. We admired the 19th century facades with attractive ironwork and colorful tiles.

The Star Chapel - what a pretty name!

The male and female statues marked Triana's love of flamenco.

As Calle Pureza cut through the historic center of Triana, we made sure to stroll down the very attractive street which had more ironwork balconies and colorful doors.

This was one of the many traditional neighborhood grocers we passed that also functioned as neighborhood bars.

The Chapel of Santa Ana, nicknamed the 'Cathedral of Triana,' was the home of the beloved Virgin statue called Our Lady of Hope of Triana. The construction of the church dated from 1266 during the reign of Alfonso X, the king of Castile and Leon. It was the first Christian church built in Sevilla after its conquest in 1248 from the Muslim Moors.

The magnificent High Altar was created in 1542 and was completed with 15 paintings between 1544-1556 and showed the lives of St. Joachim, St. Anne and the Virgin Mary.

The Virgin statue was such a major deal in Sevilla that, on meeting someone, it's the norm to question what football team they follow but also which Virgin Mary they prefer! The top two are the Virgen de la Macarena and this one, La Esperanza de Triana - I was so glad we'd now seen both! On the Thursday of Holy Week, it's a battle royale of the Madonnas, as Sevilla's two favorite Virgins are both in processions on the streets at the same time.

Chapels lined the naves of the church, each fantastically luxurious.

The Chapel of St. Christopher:

The choir stalls were completed in 1619-1620. The iron railings were cast after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake that so affected Sevilla.

This tombstone with the partially destroyed name of the buried person was the first known work in the city by Niculoso Pisano whose work we'd just seen at the Ceramics Museum. The tombstone featured 32 tiles in the tin-glazed pottery technique and included the date it was made 1503.

We peeked in the wannabe cathedral's crypt before viewing even more chapels.

Never had we been in a city before Sevilla that had such fun to look at murals on storefronts.

After having spent several thoroughly enjoyable hours in Triana, we walked back across the river to Sevilla on the Puente de San Telmo. Behind me was the Gold Tower we'd seen earlier.

As this was our last afternoon in the totally charming city of Sevilla, we wanted to make sure to see the General Archives of the Indies before flying on to Lisbon, Portugal, the next morning. But first we got sidetracked by this remarkable flamenco dancer in the square by the Alcazar. It was a riveting performance with no accompaniment; a one-man show with his doing the dancing, the rhythmic clapping and also some singing.

The General Archives houses historic papers related to Spain's overseas territories. Its four miles of shelving contained 80 million pages documenting the once-mighty empire. The archives were located in the Lonja Palace, one of the finest Renaissance buildings in Spain. It was designed by the same architect who was the principal designer of El Escorial, the historical residence of the royal family we visited north of Madrid several weeks ago.

Originally this was a market for traders, in effect an early stock market. As Sevilla was the only port licensed to trade with the New World, merchants came to the city from all over Europe and thereby established it as a commercial powerhouse. By the end of the 1600s, however, Sevilla's fortunes went downhill after suffering from plagues and the silting up of its harbor. Cadiz then overtook Sevilla as Spain's main port and the building was abandoned in 1717. It was re-purposed in 1785 as a storehouse for documents the country was quickly amassing from its discovery and conquest of the New World.

What fun climbing the extravagant marble staircase to the first floor!

At the top was a huge 16th century security chest that was intended to store gold and important documents. Its elaborate locking mechanism which filled the top lid could only be opened by following a set series of twists, pulls and pushes in order to keep out prying eyes and sticky fingers from its valuable contents.

Even though none of the documents were of course available to see, it was still incredibly impressive just walking through the galleries and imagine the stories hidden behind the massive cases in each of the three galleries.

We were lucky that the Archives had a special exhibition of paintings by native son Bartolme Murillo. The General Archives of the Indies was the first building to house the Academy of the Art of Painting, the city's first art college, which was founded in 1660 by a number of Sevillian artists, including Murillo. The exhibition of three of his works marked the 400th anniversary of Murillo's birth.

The Ecstasy of St. Francis of Assisi, circa 1645-1646, belonged to a series painted for the small cloister of the friary of San Francisco in Sevilla. It is regarded as the first major commission by the young Murillo who wasn't even thirty and was still making his name in a city with many highly skilled, master painters.

We were delighted to discover that there were after all a few precious maps and documents we could view as we'd thought they were all hidden away from public sight.

A few maps proved of particular interest to Steven and me. The first was one of Quebec City in 1699.

A map of the Mississippi River in 1699:

On our way back to the hotel, we decided to do some last minute window shopping along Calle Tetuan where old time fashion standbys bumped up against fashion-right boutiques. The first to catch our eye was Juan Foronda which has been selling flamenco attire since 1926.

A few doors away was the flagship of Camper, the Spanish shoe brand that's become a worldwide favorite.

The rest of the street introduced us to mainly Spanish brands such as Massimo Dutti, Zara and Mango.

Since my English mother inherited some antique carriage clocks, I have had a fondness for old clocks. I was therefore quite delighted when we noticed El Cronometro where master watchmakers have been doing business since 1901 in the clock-covered, wood-paneled shop.

Close by was Sombrerio Maquedano, a wonderful shop for hat aficionados. The shop claimed to be the oldest hat seller in Sevilla and possibly all of Spain.

Since first arriving in Spain six weeks ago from Kazakhstan, I'd been amazed by the exquisitely made baby clothes we saw in several Spanish cities. Never had I seen such luxurious and adorable baby clothes before. If you're a mom or grandma, BuBi would be the place to go to indulge a wee one as long as you don't object to spending about $30 for a pair of booties.

Thank goodness three of our four children all got married within ten months of each other in 2017 and 2018 as otherwise it would have been a lark to look at the classic wedding dresses in the shops along Calle Luna.

If neither adorable baby clothes nor wedding dresses interest you, what about flamenco dresses?! Local women save up to have custom-made flamenco dresses made for the April Fair as they're considered an important status symbol.

After spending more time in Spain than in any country we've ever visited, I knew it would be hard to bid adios to a nation I'd grown to love from the time we landed in Barcelona in late October and made our way through most of the fascinating country from then on. There are far too many highlights to possibly enumerate here. I hope you've had a chance to read at least some of the preceding posts to see what grabbed us as we traveled far and wide by car and then bus through a country that has known such troubled times with its own Civil War, yet a past steeped in history that draws tourists from all over the world to its exciting shores.

Next post: On to Portugal, a country we'd both wanted to visit for some time.

Posted on April 3rd, 2019, from our home in Denver's suburbs.

Gorgeous churches make me appreciate the divine in the human spirit.

ReplyDeleteHow eloquently written, Andrew! Thanks for taking the time to read the post and post your comment. Love, Annie

ReplyDeleteIntricate ceramics, opulent chapels , historic maps (even of Quebec city) and brilliant designer fashions .. what a day you had .. thanks for sharing it with us :)

ReplyDeleteLina,

ReplyDeleteWe really loved our time in Sevilla for all the reasons you mentioned and so many more, Lina. It's a glorious city full of charm at every turn - just make sure you keep an eagle eye on all your belongings at all time unlike us and you will have the time of your lives there.